We are rapidly approaching a world with ubiquitous wireless internet. We can be connected wherever we are, and we can stay productive on the go.

Though connectivity is increasingly prevalent, it is also increasingly unreliable: wireless networks are not as stable as their wired forbears. Users are often stymied by latency, packet loss, and limited bandwidth. Recall Gmail on a flaky connection. When will it load? Is my inbox up to date? Did my email actually send?

In Superhuman, we handle unstable connections in two important ways:

- We carefully monitor all network activity and keep an internal model of "is the internet working?"

- We clearly and non-intrusively convey this state to the user. We reassure them that they can keep on working.

Together with our robust offline architecture, these ensure that users always understand the state of the network, and that users never lose work.

Offline detection

At first blush, offline detection may seem simple. Surely there's a browser API?

Yes, in theory, there is: navigator.onLine. But in practice, you would quickly find that it is not truthful enough to be useful. In particular, it has the following issues:

- It returns true when there's a local network connection, even if there's no internet connection;

- It reacts too quickly to transient states like switching networks or resuming from sleep;

- It can sometimes return false even when the internet is available.

The inescapable reality is that networks fail in many ways. You could be completely disconnected. You could have insufficient bandwidth to do useful work. You could even be on a hotel hotspot that only allows access to certain sites. From the perspective of a Superhuman user these are all the same: some emails haven't sent, and some haven't been received.

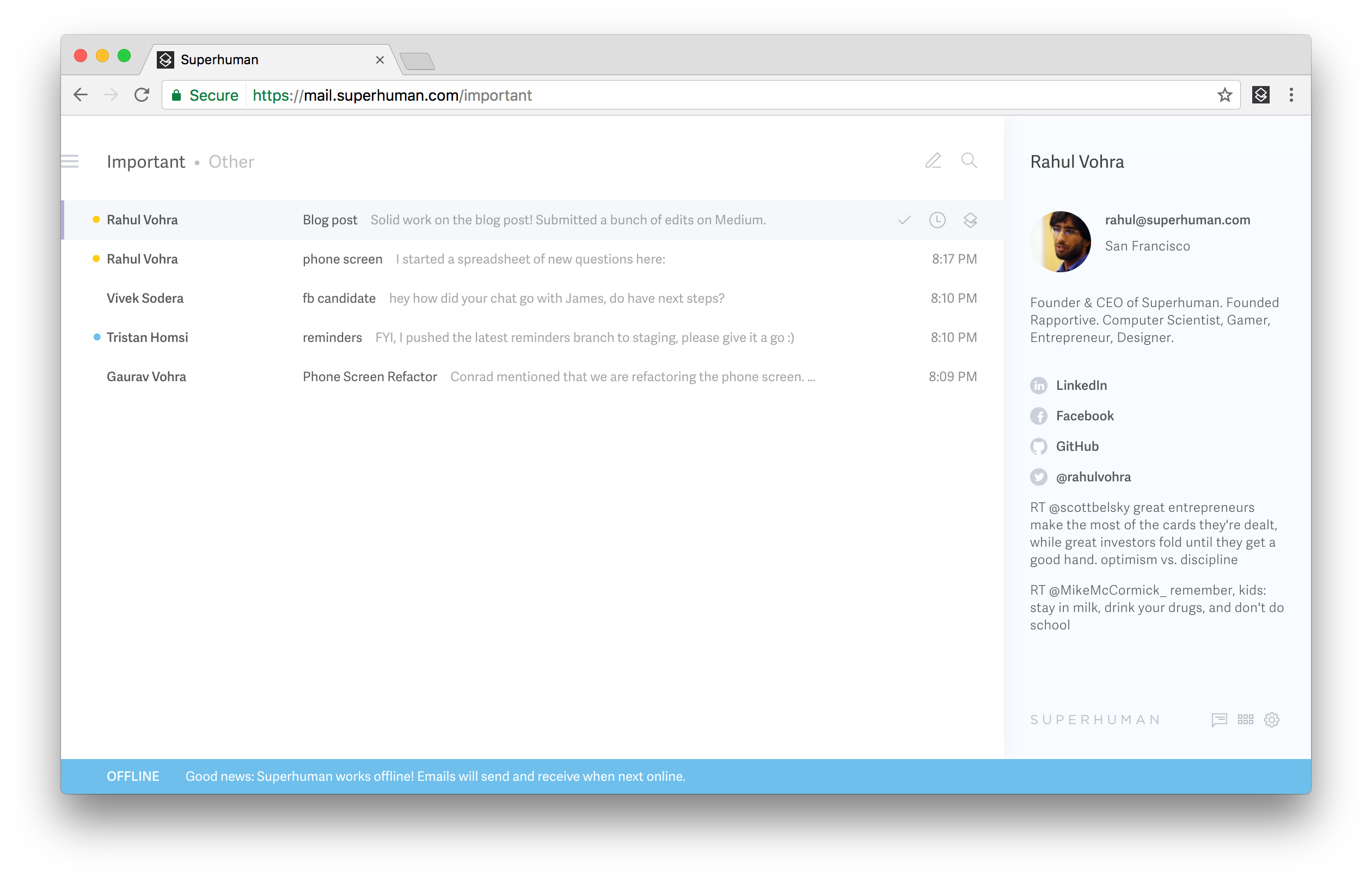

In order to communicate this in the product, we monitor all network activity and maintain an internal model of "is the internet working?". If this model indicates that any of our dependencies is offline, we show the blue offline bar.

Simplifying the mental model

We want to reduce the number of states in the product, as this reduces both the number of things the user needs to think about, and also the number of code paths we need to test. We therefore treat every kind of network failure as "offline"— and we also ensure that the entire product is considered offline.

All HTTP and WebSocket requests are made via wrappers that do three things:

- If our internal model says we are offline, pre-emptively abort the request with an OfflineError. This avoids unnecessary failed requests and preserves battery life.

- If the request times out or fails at the network level, abort the request with an OfflineError and update our internal model to indicate that the appropriate dependency is down. This causes the blue offline bar to appear.

- Provide a method to determine when connectivity is restored.

It is surprisingly hard to set time out limits. For example, we used to set a hard limit on how long requests could take. However, this would misfire on connections that are very high latency but otherwise mostly fine — such as on a plane. Instead, we now make heavy use of progress events, and time out requests that make no progress within 5 minutes.

Since any failed request causes the product to go offline, we can greatly simplify error handling and also be confident that our messaging makes sense.

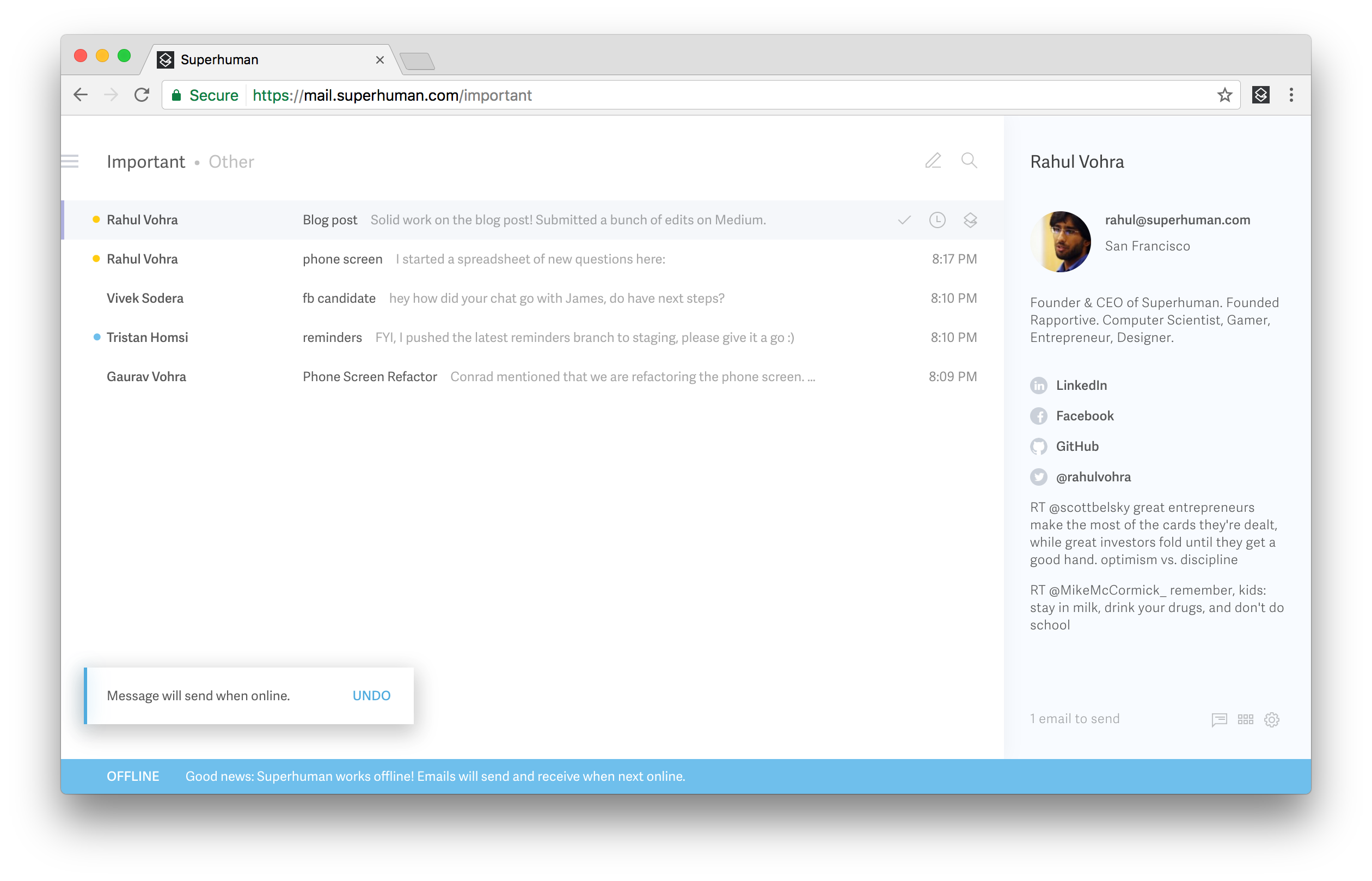

Consider sending an email whilst offline:

The "Message will send when online" notification shows if and only if the network request failed with an OfflineError. This means that offline notifications can only show if the blue offline bar is also visible. The UI will always be consistent.

Online detection

When the app is set offline by a failed request, it starts polling the dependency every 10 seconds (with a little bit of jitter). For example, after a failed Gmail request, the app will ping a certain Gmail API endpoint. And after a failed Firebase request, the app will ping a certain Firebase key.

When the app successfully contacts a dependency that was marked offline, it marks that dependency as online again. When all dependencies are marked online, the app is online once again and the blue bar disappears.

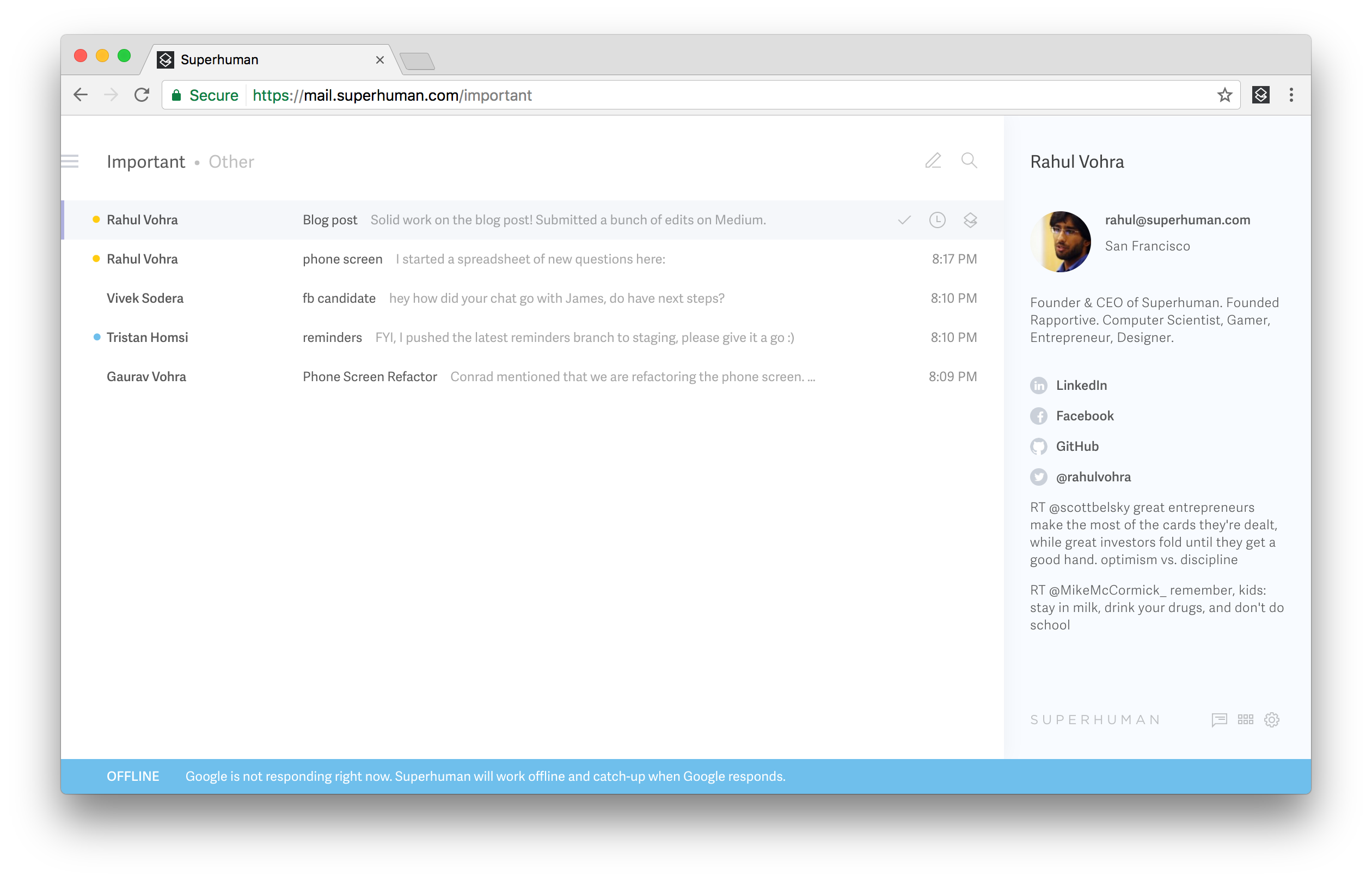

Since we poll each dependency separately, we can display which dependencies are down.

This approach has less than perfect availability in some unlikely scenarios, but it does also result in a simple programming model and a coherent user interface.

Inconsistent connectivity

On tethered connections, where some requests fail but most succeed, the blue offline bar would often flicker in and out. To help Superhuman feel more stable, we add some hysteresis: when a dependency is marked offline, the app waits 10 seconds before polling it. The bar is therefore always visible for at least 10 seconds.

We found cases where the blue offline bar would still oscillate every 10 seconds. Whilst this is better than flickering, it still gets old fast. To address this, if the app goes offline twice in quick succession, the timeout increases to 60 seconds. These numbers were picked based on how they felt: we want the bar to feel stable without sacrificing perceived availability.

Conclusion

Ubiquitous connectivity is here to stay. And whilst wireless networks are continually improving, most modern apps still do not behave well on unstable connections.

It's time to write better apps. We owe it to our users to:

- Avoid losing their data at all costs;

- Communicate clearly about the state of the network;

- Engineer network robustness into our products.

If you have any feedback about our approach please add a comment below; we'd love to hear from you.

Otherwise hold tight for Part 3, where we explain how to store and index gigabytes of data in the browser itself!