Subvocalization is how we say words inside our heads as we read them — something almost everyone does naturally. It is also called internal speech, inner speech, silent speech, or inner vocalization.

Subvocalization is common. But in productivity circles, many people claim that subvocalization is holding you back from reading as quickly and efficiently as possible.

This article will tell you what subvocalization is and how it works. We’ll cover:

What is subvocalization in reading?

Is subvocalization good or bad?

How to stop subvocalization?

FAQs

What do we know about subvocalization today?

How common is subvocalization?

Can speed reading make us more productive?

What is subvocalization in reading?

Subvocalization is the process of inaudibly articulating speech with your speech organs. It is an inherent part of reading. Think of it as the inner voice you might hear while reading.

Subvocalization involves much more than just thinking words as you read them. It involves physical body parts, including eyes, lips, throat, tongue, vocal cords, jaws, and larynx!

During subvocalization, all the muscles involved in articulating speech sounds move to evoke the sound of the word (silently) as you read it. Subvocalization is characterized by these movements, which are often too small to be detected even by the subvocalizing person.

However, the movements are the same as when we speak — NASA scientists have been able to use electromagnetic sensors attached to a subject's throat to transcribe material they are reading silently via the movement of their speech organs.

Subvocalization is a natural process that helps our brains comprehend and remember what we're reading. Muscle memory is how we learn to perform complex movements involving different muscles and body parts faster and more accurately over time by repeatedly performing those visible movements.

Researchers believe subvocalization uses mechanisms similar to muscle memory to help store and access the meanings of different words.

Research into subvocal speech was documented in 1868, when scientists began to consider thinking as "subdued speech". In 1899, a researcher named L Curtis was able to record the movement of the larynx during silent reading, and he concluded our "inner voice" while reading causes the same movement in the speech organs as saying the exact individual words aloud. Curtis believed that silent reading is the only mental activity that causes considerable movement in the larynx.

Research continued in 1950 when Ake Edfelt created an electromyography (EMG) device that could record the physical movement of all the speech organs during silent reading.

Edfelt also experimented with suppressing subvocalization, but he eventually concluded that subvocalization reinforces learning, and disrupting it could interfere with learning and development.

Is subvocalization good or bad?

Short answer: It depends.

Subvocalization is a natural phenomenon. Some researchers theorize that humans might not even be able to learn to read if we didn't subvocalize.

It's generally accepted that, because of the role it's believed to play in reading comprehension and memory, subvocalization is very useful for reading technical materials, learning new words, or memorizing material word-for-word.

However, many researchers also agree that subvocalization can limit our reading speed as it burdens cognitive resources extra.

As Stephen K Reed put it in his book Cognition: Theories and Applications –

"Although subvocalising can help us remember what we read, it limits how fast we can read. We could read faster if we didn't translate printed words into speech-based code."

In Toward a Model of Reading Fluency, S Jay Samuels hypothesized that the most fluent (and fastest) readers don't subvocalize.

"[R]eading theorists such as Gough (1972) believe that in high-speed fluent reading, subvocalizing does not happen because the speed of silent reading is faster than what would occur if readers said each word silently to themselves as they read," he wrote. "The silent reading speed for 12th graders when reading for meaning is 250 words per minute, whereas the speed for oral reading is only 150 words per minute (Carver, 1990)."

But there's no scientific consensus on whether it's possible to stop subvocalizing — or if that would help or hurt our reading skills.

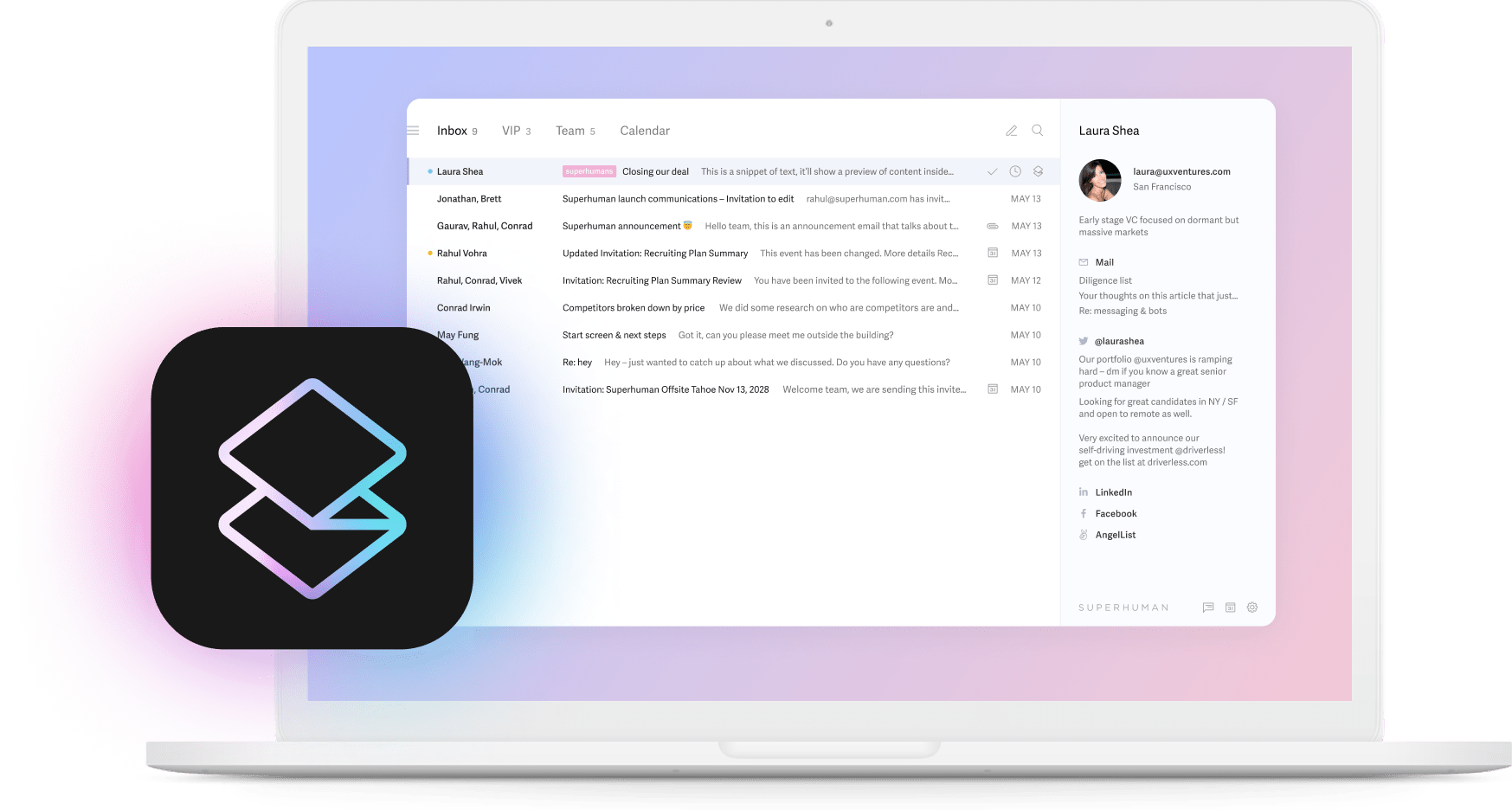

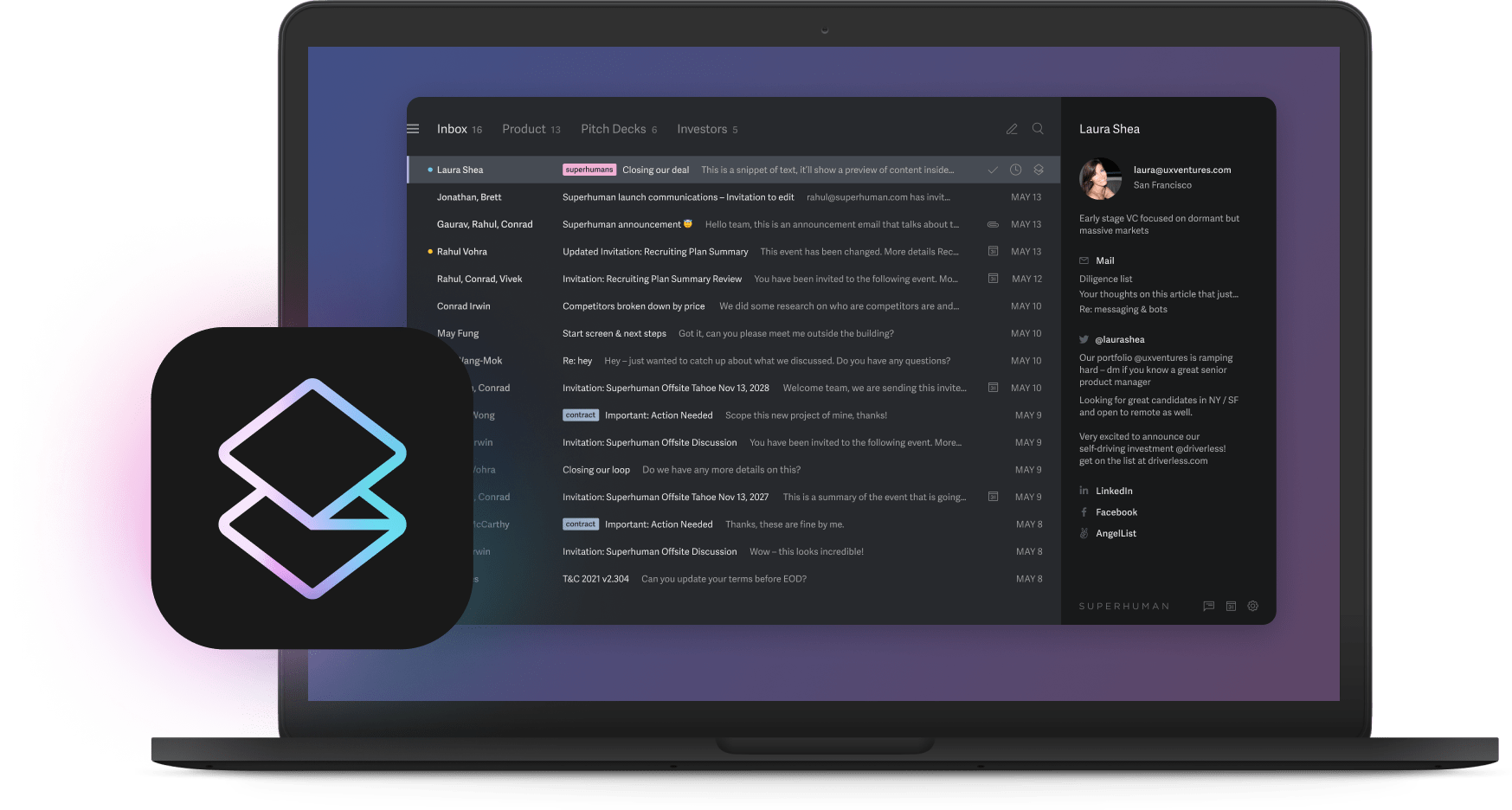

Keeping this in mind, Superhuman launched Auto Summarize – a feature that enables you to read faster and more efficiently.

With Auto Summarize, you will see a 1-line summary above every conversation. As new emails arrive, it updates instantly. If you want to see more detail, just hit M.

In most cases, you won’t even need to read the entire email. This massively increases your reading speed, helping you to move through your inbox productively.

Again @Superhuman nails it!

— Paco Cantero (@PacocanteroW) November 8, 2023

Auto Summarize is a no-brainer!

Thank you, guys!

You just don't make me much more productive. You make me happier!

🔝🙌

How to stop subvocalization?

While micro-muscle tests suggest that we can’t stop subvocalization entirely, there are ways to avoid it and become a faster reader. Here are some practical reading and skimming tips for both speed and comprehension.

Practice skimming techniques

Not everything you read needs to be read deeply. Some of it can be skimmed. And while science tells us that speed reading is unlikely to be possible, speed skimming is certainly within reach for many people.

Skimming is scanning text to try to pick up selective words or ideas. In a 2009 study, researchers tested different skimming techniques by asking readers to read essays that:

- Had the first half of the words covered

- Had the second half of the words covered

- Had the first half of each paragraph covered

- Had the second half of each paragraph covered

The researchers found that people performed better on a memory test if they read half-paragraphs, rather than just the first or second half of the essay — and that they performed just as well as people who were asked to skim an entire essay with a short time limit.

This reinforces the idea that skimming by reading just the first sentence or 2 of each paragraph can reduce reading time without sacrificing too much comprehension.

Set reading goals

Are you reading to learn about a complex new topic? Or to quickly read your emails so you can focus on essential tasks?

The type of reading you do will influence the speed at which you can do it — complex material that requires focus and enhanced comprehension should be read more slowly, focusing on subvocalization, which will help you process and remember the material.

Let’s talk about reading emails. When it comes to managing your inbox, the way you approach reading emails is crucial.

Unlike comprehending a complex topic, the goal here is speed and efficiency. Quickly scanning through emails to pinpoint critical information requires striking a balance between effectiveness and efficiency.

Superhuman’s Split Inbox feature helps with that.

Viewing all your emails in one list is overwhelming and makes it harder for Inbox Zero. Split Inbox divides your inbox into different areas of focus — based on the types of emails you receive most often. Now, you can choose a workstream and process those emails together.

By minimizing task switching, this feature streamlines your email management and saves you valuable time, empowering you to read and respond faster.

Recommended reading: How to mark all emails as read (in Gmail and Outlook)

Use a pointer

Many speed reading courses recommend using a pointer, pencil, or your finger to guide your eyes through text at a predetermined rate (say, 1 line per second). This is one part of speed reading backed by science because it's not always easy for our eyes to focus on a piece of text.

Eyes are constantly in motion, and using a pointer can help stabilize natural eye movement and keep your eyes moving smoothly across the text as you read. This may feel unnatural at first and might slow down your reading in the beginning.

But over time, practicing steady eye movement will train your eyes to move quickly and smoothly every time you read, rather than jerking or moving backwards.

Another way to train your eyes is by using dark mode when reading on a device. Dark mode changes the usual colors on screens from light to dark backgrounds. This reduces eye strain and makes reading more comfortable.

Minimize lip and throat movement

Subvocalization involves the muscles associated with speaking, like those in the lips and throat. Minimizing these movements while reading encourages your brain to focus more on understanding the text without relying on inner speech.

You create a quiet mental environment that allows you to absorb information more efficiently. This shift in focus from inner speech to silent reading can enhance your reading speed and comprehension, making it easier to grasp the meaning of the words without subvocalizing every one of them.

One way to do this is to chew gum or hard candy. This keeps your mouth occupied, minimizes lip movement, and promotes a more focused reading experience.

Do silent reading

When you read without vocalizing the words in your mind, you break the bad habit of pronouncing each word internally. This allows your brain to process information directly without relying on the additional step of inner speech.

Silent reading helps stop subvocalization because it encourages a more direct connection between your eyes and brain. Instead of translating the sight of words into spoken language inside your head, you train your mind to comprehend the meaning silently.

This shift in reading approach can improve reading speed and comprehension by eliminating the need for subvocalization, making the reading process more efficient and focused.

Read things you love

Even the most competent readers read slowly if they find the material boring. As you develop your speed reading habit, seek out material you enjoy reading and learning about and use it to practice these techniques. Over time, it will become easier to apply them — even to reading material you don't love.

Recommended reading: What are the easiest fonts to read?

Wrapping up

Learning to read faster can increase your productivity by helping you finish reading-based tasks in less time. But speed isn't always the most important thing when it comes to reading.

As you practice these reading techniques, remember that speed reading isn't the opposite of subvocalization. The key to being the most efficient reader is balancing the two: reading quickly while gaining the comprehension and memory benefits of subvocalization.

Superhuman has you covered when it comes to reading and responding to emails. Whether it’s Auto Summarize, Split Inbox, or other features, Superhuman lets you triage your emails to prioritize important messages and speed up your email management workflow.

FAQs

What do we know about subvocalization today?

Today, subvocalization is considered one of the components of Baddeley's model of working memory, a proposal made by English scientists Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974. It's their theory that the physical movement during subvocalization is part of the "phonological loop" that helps commit what's being read to your short-term memory.

Scientists are still learning about exactly what's happening in the brain during subvocalization, but they have found that subvocalization causes brain activation (detected via fMRIs) in multiple areas. One of the main areas activated by subvocalization is the Broca's area of the brain, which is the part responsible for speaking.

How common is subvocalization?

Subvocalization is most people's default state when reading silently. Deaf people who learned sign language have even been documented to "subvocalize" through tiny, involuntary movements in their fingers and forearms.

This research helps explain why most people's average reading speed — typically 200-250 words per minute (WPM) — is so similar to their speaking pace, typically 200-240 WPM when speaking quickly. When people subvocalize, they generally can't read faster than they can talk.

Recommended reading: How to read faster: 8 best speed reading apps

Can speed reading make us more productive?

On any given workday, most of us spend a lot of time reading work materials, research, memos, Slack messages, emails, and more. Getting through all that reading faster would create more time for other tasks, thus making us more productive, right?

That's the idea behind speed reading courses and tools, some of which have claimed they can help the average person read thousands of WPM.

The first popular speed reading course, introduced in 1959 by Evelyn Wood, claimed that people read slowly because they don't read efficiently. The key to speed reading, Wood said, was learning to make fewer back-and-forth movements with your eye, instead taking in more words — several lines of text — with each glance. That idea is also the basis behind apps like SpeedRead With Spritz, which are designed to train your eyes to take in more words in less time.